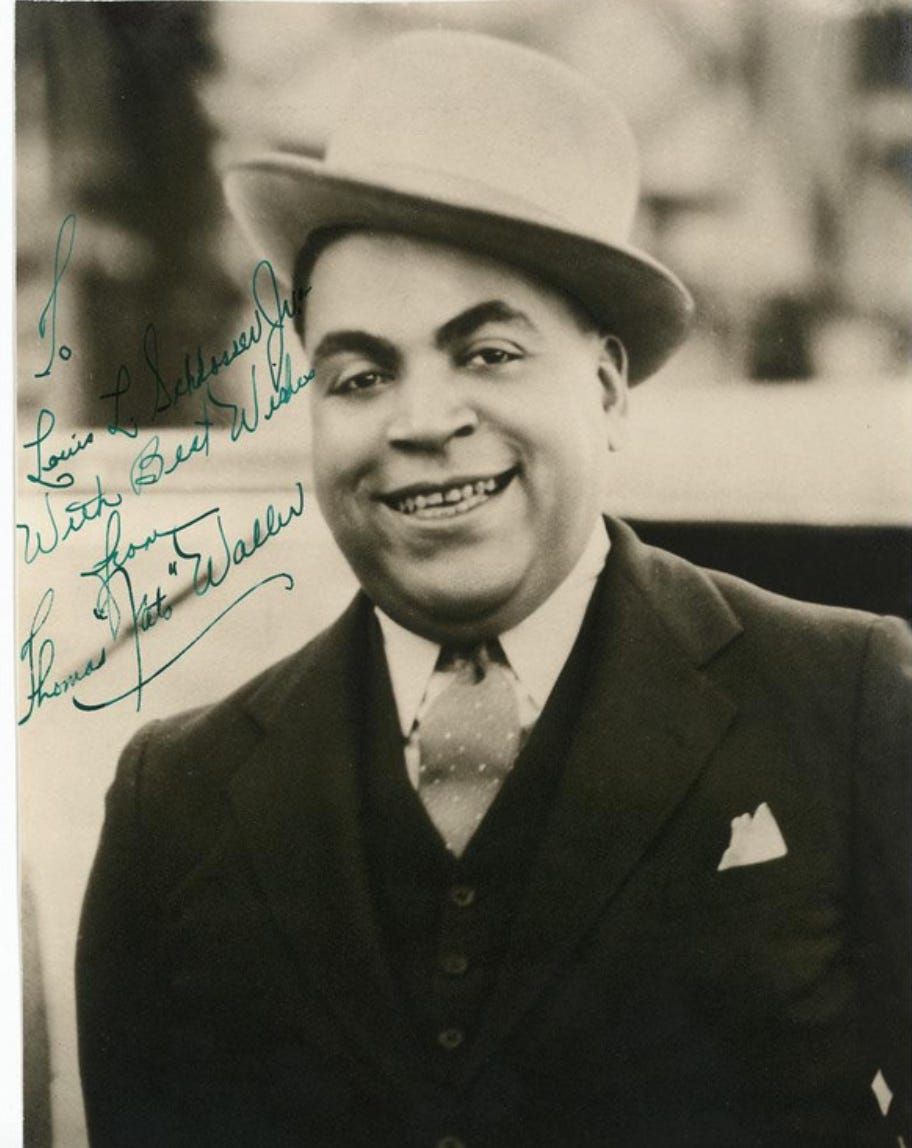

In tribute to the great Fats Waller on his birthday, here’s a transcript (slightly edited) of the podcast I did on July 12, 2024 (Ep. 22 - “Fats Waller”). I’ve added brief clips of the music where it fits, but you may also want to listen to the whole show.

Thomas “Fats” Waller was a preacher's kid from Harlem, New York. Born on May 21, 1904, he started learning the piano from his mother and taught himself pipe organ in his father's church. Fats discovered jazz early in life, sneaking into Harlem clubs and listening to the great pianists who came before him, taking formal lessons from the great stride pianist and composer James P. Johnson.

Well, his father was none too pleased. As a Baptist preacher, Mr. Waller took a dim view of jazz, or as he called it, “the devil's music.”

But that didn't stop Fats. He learned to play ragtime and then stride piano — in some cases better than any of his mentors — in Harlem clubs. And as soon as he could, he started to make a living on the organ at age 15, playing for silent films at the Lincoln Theater in Harlem.

It was said that Thomas Fats Waller ate more food, drank more liquor, recorded more jazz records in his time — and just had more fun — than any other performer, before or since.

Listening to him, who could doubt that?

A couple of examples of Waller’s piano playing. First, Fats Waller at his loveliest, recorded June 11th, 1937, on a tune called I Ain't Got Nobody by Spencer Williams. And then as an homage to his teacher, James P. Johnson, Waller playing Johnson’s Carolina Shout, recorded in 1941.

In 1919, Fats' mother Adeline died. At about the same time, he began learning James P. Johnson's piano technique by shadowing Johnson’s piano rolls.

Fats would sit at a special player piano with a locking mechanism and he'd put his fingers over the depressed keys as the roll played, and then lock it by sliding the mechanism. That way he could “shadow” Johnson’s playing. And he'd do this for hour after hour. One day, he finally got his nerve up to meet Johnson, introduced by a mutual friend.

Johnson could see Fats' enthusiasm and took him as a regular student. Fats would spend so much time with Johnson, both at Johnson's house and in the clubs that at one point Johnson's wife, Lillie Mae Wright, asked Fats, “Don't you have a home to go to, son?”

I mentioned that Fats got a job playing the theater organ for silent movies at the Lincoln Theater in Harlem at age 15 — this for the lordly sum of $23 a week. Waller was self-taught on the organ.

He used to hang out at the Lincoln Theater to watch other organists play. He watched their feet and their hands and what they did with various stops and levers. It's pretty amazing when you think about it. Here are two early examples of Fats at the organ.

That’s All (1929) and Sugar (1927) with blues singer Alberta Hunter.

Fats Waller made his first recordings in about 1922 for OKey Records (Clarence Williams' outfit).

In 1925 he wrote Squeeze Me, which became Waller’s first hit. Squeeze Me was based on an early kind of “naughty” blues. Bessie Smith liked it and recorded it, as did Meade "Lux" Lewis. Here’s an extract from Fats’ PG version, recorded in 1939:

Squeeze Me, Waller’s first big hit composed in 1925; from a recording done in 1939. The song is credited to Clarence Williams, the publisher, but Andy Razzaf has also claimed credit, and he's probably the more likely author. We heard Fats Waller and His Rhythm (Fats Waller, John Hamilton, Trumpet, Gene Cedric, Clarinet and Tenor Sax, Cedric Wallace, Bass, John Smith, Guitar, and Slick Jones on Drums). Listen to the full version on AJBB #22, “Fats Waller.”

Fats Waller copyrighted over 400 songs, and wrote many more. Many he gave away or sold for very little. Many of these songs were co-written with his closest collaborator, Andy Razaf.

Razaf was born in Washington, DC. in 1895. He was related to an actual queen — of Madagascar — and his grandmother on his father’s side had a last name of Waller — no relation to Fats, just one of those amazing coincidences. Razaf was raised in Harlem, in Manhattan, and at the age of 16, he quit school and took a job as an elevator operator at night so he could continue to write poetry and lyrics during the day.

When he wasn't operating the elevator, Razaf spent many of his nights in the Greyhound Lines bus station in Times Square, where he picked up his mail at the Gaiety Theater office building — considered the black tin pan alley of the time. And it was there that he met Fats Waller. He and Fats wrote a show together in 1929 called Hot Chocolates.

One of the songs from the show was What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue? It was pretty remarkable stuff for 1929 — or any year.

Louis Armstrong, who sang from the pit in Hot Chocolates, recorded (What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue? on July 22, 1929, in New York City. Initially, Edith Wilson performed the song in the show, but Armstrong’s version, released in August 1929 (as the B-side of Waller’s and Razaf’s single, "Ain't Misbehavin’”) was something of a sensation.

We'll follow that with Waller's other 1929 hit, Honeysuckle Rose, from an off-broadway revue called "Load of Coal,” playing just down the street at Connie's Inn.

“Ladies and gentlemen, just to let you know that I paid my alimony, and I ain't misbehaved.”

Here’s one more Fats Waller recording. It's Then I'll Be Tired of You. It's a particular favorite of my wife’s and mine since it was played at our wedding.

While traveling aboard the famous Los Angeles–Chicago train, the Super Chief, near Kansas City, Missouri, Thomas Fats Waller died of pneumonia. It was estimated that more than 4,200 people attended his funeral at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem (where his father was once minister), prompting Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who delivered the eulogy, to say that Waller "always played to a packed house."

Happy birthday, Fats.

From At the Jazz Band Ball: Fats Waller, Jul 12, 2024

Copyright 2025 Kevin McLaughlin